DAY 1

Raymond sat alone at the kitchen table. Permitting himself a few moments of respite

between chores, he stared blankly at the wall, allowing his mind to wander. It had been three weeks since his master had

left for his expedition after promising to return in a matter of days. Such conduct was unlike his master who’d proven

himself fastidious, sometimes ruthlessly so.

Without his presence, the modest house felt empty, with one of its

bedrooms and the master’s study now unoccupied.

Except of course for Raymond.

A scarecrow by birth and a servant by nature, Raymond busied

himself with housework just as his master had instructed before he had

departed. Gliding from room to room, he

rendered the place spotless with the skill and quiet dignity of a practiced

domestic servant. Initially, he

complied, fearing punitive measures, but as the days turned into weeks, he

undertook his chores with intense fervour.

What else would I

do? How else do people occupy their time

except in service to their masters? he thought as he waxed the wooden

floorboards of the corridor.

All food related chores were the first to disappear – as a

scarecrow, Raymond had no need to eat.

It was a pleasure denied him by his creator, though he had often

marvelled at the transformative nature of food, its innate ability to bestow

comfort and satiety. First tier chores

such as sweeping, dusting and the washing of dishes soon gave way to more

complicated, second tier tasks like washing windows, cleaning gutters and

re-tiling the roof. Using a not

inconsiderable amount of elbow grease (if his body had produced such a

substance), Raymond maintained the house spectacularly.

One afternoon, there came a knock at the door. Raymond was immediately suspicious, knowing

that his master would never knock as he rarely left the house without keys. Curious, he opened the door to reveal a

surprising sight – a giant stick insect, stood upright, attired in formal suit

and tie.

‘Good afternoon sir’, said the stick insect as he extended his

arm in greeting, ‘My name is Julius Wallwork, Esquire. Might I have a moment of your time?’

‘Of course’, stammered Raymond, as he shook the man’s hand

and ushered him into the entranceway.

Remembering his manners, Raymond struggled to suppress his fascination

with the strange man’s appearance. There

were of course many and varied sentient creatures in the kingdom, but he had

lived a life mostly indoors and had rarely been exposed to such zoological

diversity.

Julius Wallwork made his way inside the house, proceeding

down the short corridor and into the kitchen where he politely sought

permission to sit at a small table.

Raymond replied in the affirmative as Julius placed a scroll and a small

wooden box upon the tabletop. Through

his buttoned shirt and sleeves, Raymond could catch glimpses of the man’s

peppermint coloured thorax.

‘Mister Raymond, I represent Angus & Altman. We’re solicitors, specialising in property

management and estate planning in this general vicinity’.

‘Okay’, said Raymond hesitantly, still wondering why such an

elaborate fancy man would stoop to converse with a lowly scarecrow.

‘I’m afraid it’s my sad duty to inform you of the death of

your master, Kevin’, Wallwork announced as he presented Raymond with the box

that he had brought with him.

Raymond carefully opened the receptacle. Inside it was a human heart, the organ

partially desiccated and decorated with traces of dried blood about its four

chambered structure. The heart belonged

to Kevin, and, had evidently been torn out by whatever agent had caused his

demise.

‘I realise this may be a gruesome sight for you, but the

presentation of a heart is customary in this circumstance, especially where the

transfer of property is concerned’.

‘Transfer?’ asked

Raymond, still enthralled by the grisly sight of his master’s heart in a

box. He was struck by the notion that

his master even possessed such an organ, given his sour disposition and proclivity

for cruelty.

‘Kevin’s death changes things for you considerably, Mister

Raymond. In the absence of an heir or

suitable inheritor, the deed to the current property – this house – legally

reverts to any other current occupants.

In this instance – that’s you’.

Julius unfurled the scroll across the kitchen table. It was an ancient looking document, its text

hand written in slanted script that was difficult to read. At the top of the scroll, in letters larger

than the rest were the words ‘Life Transfer Document’, and at the bottom, a

straight line presumably reserved for a signature. At the centre of the scroll was a single

human eye, which, as soon as the scroll had been unrolled, blinked into

existence, darting about the room.

Standing to leave, Julius provided Raymond with a final set

of instructions.

‘As per local law, you have ten days to sign the document,

after which point this house and all its contents will become your legal property. Should you fail to sign in the allotted time,

custody of the house reverts back unto itself, and your rights as a tenant

within it will be rescinded’.

Offering a polite bow to excuse himself, Julius made his way

to the front door, as Raymond trailed behind him. This turn of events had been so unexpected

and he was brimming with questions for the stick insect lawyer. But, as evidenced by the brevity of his

visit, his time was too valuable for him to linger a moment longer than

necessary. Raymond tried to think of the

most pertinent question to ask, but instead his mind went blank.

‘But what about my master?’,

he blurted out almost reflexively.

‘Your master is dead, Mr Raymond. You are your own man now. I suggest you get used to it’.

‘My own man…’ Raymond repeated to himself softly as Julius

left the premises. It was a tremendous

concept to digest.

DAY 4

A few days had passed since the lawyer had called on

Raymond, casually breezing into his life and leaving seismic new ideas at his

feet. Though not outwardly exhibiting

any signs of distress, Raymond had been quite shaken by the visit, and decided

it was best to simply ignore everything he’d been told. As before, he proceeded with his chores, dusting

surfaces that were already clean and preparing the house for a master that

would never return.

Yet every time he found himself in the kitchen, he’d see the

expectant scroll, its unnerving eye watching his every move, waiting for him to

either sign (or not sign) his name at the bottom of the page. The very sight of the offending eye reminded

him that things had changed and that Kevin wasn’t coming back. Not only was he a free man, but if he signed

the scroll, he would be a home owner.

Sat in his chair – a brief pleasure that he occasionally

allowed himself – Raymond pondered the concept of freedom. What did it mean? Kevin had captured and removed him from his

family at such a young age that he had never known any other life. What would he do with his time? He thought about his family and briefly considered

paying them a visit. From what little he

could remember they lived in a small enclave just beyond the forest, but, given

the short lifespan of most scarecrows they were most likely deceased. Later, as he examined the document once more,

he pondered the unusual nature of its title – Life Transfer Document. Was

the house somehow alive, and if so, was it a slave to Raymond?

DAY 5

After spending the day washing linen, Raymond was met with

the uneasy feeling that his tasks no longer felt as fulfilling as they once

did. As dusk arrived, he allowed himself

to stand on the front porch of the house and admire the beauty of the plants

and trees around him. Previously, such

stolen moments had been forbidden, but now Raymond wondered if he could occasionally

permit himself some rudimentary moments of pleasure.

‘Beautiful evening, isn’t it?’ came a voice from a few feet

away.

It was Mrs Gale, the next-door neighbour who was sitting on

her own porch evidently doing precisely what Raymond had been doing as well.

‘Oh, hello Mrs Gale’ offered Raymond politely.

He had rarely had occasion to speak with the old woman,

forever beholden to his duties, but he liked her. She always spoke to him warmly and, despite

being confined to a wheelchair, nearly always displayed a sunny demeanour.

‘Kevin is dead’, he blurted out without thinking.

‘I know, dear. I felt

him die. A shame really, such an angry

young man’.

Kevin had often been churlish with Mrs Gale, annoyed by her dumpy

countenance and her propensity for dispensing unsolicited homespun wisdom.

‘I was visited by a lawyer who said that I’d inherit the

house if I sign a scroll’.

‘Was that the green gentleman I saw the other day?’

‘Yes, that’s right’.

‘So, what are you waiting for, dear? Sign the contract, and we’ll be neighbours

fair and square’.

‘It’s not that simple’.

‘Sounds simple enough to me.

Do you need to borrow a pen?’

‘It’s not that – I already have a pen. I just keep staring at that scroll, and it

stares back at me. Without instruction,

I’m frozen and afraid. I’ve never known

choice, or decision. I’m scared of doing

the wrong thing, so instead, I do nothing at all. How do you know what to do Mrs Gale?’

The old woman looked pensive for a moment, taking a few

seconds to formulate a thoughtful response.

‘I’m not sure, dear.

I suppose I use past experience to guide me. You have to make your own future – one day at

a time’.

‘But I have no

past experience. My whole life I’ve been

a slave’.

‘Well then’, smiled Mrs Gale, ‘Its time you started making

some choices, dear’.

She tilted her head in the direction of the nearby tree line

where, almost as if the universe had anticipated his need, a rat with a bindle

sauntered past their houses. He walked

upright, with his possessions slung across his shoulder. Moving cheerfully despite his bedraggled

appearance, his feet were bare and blistered and his eyes looked weary from

travelling.

Sensing a new emotion coalescing within him, Raymond tried

his utmost to comprehend the new sensation.

Impulsiveness – the need to act spontaneously and without

forethought. The sensation travelled upwards

from his belly, up into his chest and into his mouth where it eventually formed

words.

‘You there’, he called out to the rat man, ‘Do you need a

place to live?’

DAY 8

Life with Percival was very different to life with

Kevin. Transient by nature, Percival

just so happened to be walking past Mrs Gale and Raymond at the very moment in

which Raymond had been inspired to make a choice. Acting in an uncharacteristically spontaneous

manner, he’d invited the wandering rat to cohabitate with him. It was a perfectly equitable arrangement - the

rat man occupying Kevin’s former bedroom which had remained vacant for some

time. The terms of his tenancy were

loosely defined, with no fixed end point agreed upon in advance. Refusing to accept any of the rat man’s

money, Raymond agreed to be paid in household duties, and his new housemate

readily obliged.

The perfect lodger, Percival’s jovial demeanour and

colourful tales from the road made him a pleasure to be with. For his part, he was happy to have a stable

home, at least for a time. He treated

Raymond with decency, never once verbally scolding him, threatening his life or

setting fire to his extremities.

After a few days and nights, the two housemates had settled

into an agreeable routine. They would

share a meal together, recounting humorous or significant moments from their

day. Percival had recently discovered

what he considered to be a superlative fishing hole and frequently returned to

the house with fresh Twilo fish.

Raymond, sans digestive system, would happily sit with his rodent

companion, so as to politely share the dining experience. After they had cleaned their plates, they

would retire to the living room and read, or sometimes listen to music. One such evening, as Raymond read, Percival

smoked the bark of the Carboline tree.

‘Why do you smoke that?’, Raymond asked.

‘Because it makes me happy’, replied Percival flatly.

Raymond had not been prepared for the simplicity of his

companion’s response.

‘What is

happiness?’, Raymond ventured, after a few moments.

‘Happiness is that which I pursue’.

‘Why?’

‘Because it is the purpose of my life. To find those things and people that bring me

the greatest joy’.

‘What does it feel like?

Happiness, I mean. Is it painful?’.

Percival took a drag of the burning bark and allowed his

gaze to melt away into the distance as his mind conjured images of past

pleasures.

‘It feels like a stillness of my thoughts and an easiness in

my body’.

‘That sounds complicated’, lamented Raymond.

‘It’s not’, replied Percival who now turned his attention to

Raymond whose questions seemed unusually wistful, ‘What makes you happy?’

‘I’m unsure what will make me happy’.

‘What have you tried so far?’

‘Nothing. I can’t be

certain that any of the things I choose will lead to happiness and so I choose

nothing. Instead, I simply sit in my

chair and stare at the wall, and that in itself seems like an indulgence’.

‘Is that why you haven’t signed the scroll?’

‘Yes. I’m not sure if

it’s the correct course of action’.

‘You know I’d sign it for you, but the eye sees all. And besides, for me, a house would only be an

impediment to my happiness’.

Though his intuition where people were concerned was

underdeveloped, Raymond believed him.

There was no conceivable way that a creature such as Percival would

settle down as a home owner. He would

stay for a while, but his inquisitive nature and nomadic spirit meant that the

road ahead was always calling his name.

‘Perhaps it’s time you sought advice from a higher power?’,

offered Percival with a raised eyebrow.

DAY 9

The following day Raymond decided to heed Percival’s

suggestion. Over breakfast, he informed his

housemate that he intended to visit the area’s foremost seer, the Lady in

Waiting.

‘Okay then, but be careful’, cautioned Percival, ‘You want

to keep well clear of those dreadful Simians’.

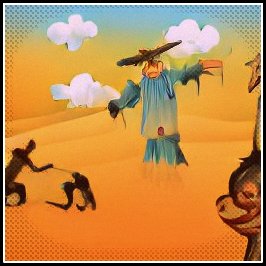

He was right to be apprehensive – Simian Sands was a valley

occupied by a tribe of crazed apes, well known for their extreme violence towards

intruders. Best avoided, they were

rumoured to have all been driven mad through exposure to industrial waste.

Summoning his courage, Raymond left the house for the first

time in many years. Using a crude map he’d

found in Kevin’s writing desk, he made his way through a brief wooded section,

past several physical landmarks to the Lady in Waiting’s residence. His former

master had availed himself of her services often enough, holding her counsel in

high esteem. Raymond hoped that she’d be

equally useful to him as he trekked through the forest, trying his best to stave

off the overwhelming fear he felt at so many new sights and the ominous sounds

of the screech owls above.

Soon enough, a large, hollowed out tree presented

itself. Its proportions were gigantic,

with its base several meters in diameter.

It was the largest tree Raymond had ever seen, although he had not had

cause to see very many in his life. He

entered warily, through a passageway just large enough for him to squeeze his

body. As the darkness of the inside of

the tree enveloped him, he nervously announced himself, expectantly hoping that

the lady residing within would reassure him with an acknowledgement. Proceeding further into the tree he came to a

generous circular space, dimly lit by candles.

‘Enter, and be seated’, came a voice from somewhere inside

the room.

Raymond’s eyes darted about until they landed upon a human woman

sitting at a small wooden table. She

wore a faded Victorian gown, frilly and ornate and had laid out a deck of tarot

cards on the table before her. He

approached, intending to occupy the vacant seat opposite the lady, but as he

moved closer, he realised he’d failed to observe a key feature of the woman, or

rather, a lack thereof. She had no

head. By the looks of things, it had

been shorn clear off - by what method he was unsure - but the wound appeared

cauterised and bloodless.

‘Be seated’, the woman repeated in a clear tone that only

now Raymond realised was occurring completely in his mind.

This was the Lady in Waiting, and even though decapitated,

she was still able to communicate using only her thoughts. Raymond obliged and took the seat, consciously

averting his gaze from her headless stump.

Slowly, deliberately, the lady began turning over her strange tarot

cards. The first one – The Sickly Magician – revealed

itself. Bearing the image of a

well-dressed man vomiting upon a green pasture, it made Raymond feel uneasy.

‘Interesting’, remarked the lady, mostly to herself before

turning over a subsequent card.

This one was entitled The

Pregnant Mule and depicted the eponymous creature with its belly

distended. Without a head, Raymond suspected

by the lady’s body language that she was deep in thought.

‘What do they mean?’, he asked tentatively after a few

moments of silence.

‘Crossroads’, she began, speaking clearly inside his head, ‘A

time of rebirth and great change’.

Turning over a third card, the lady let out an audible gasp

at its appearance: The Unbroken Line

– the illustration depicting a straight red line rendered in blood. The lady was silent for a moment, and without

a face, Raymond couldn’t read her expression.

‘What does it mean?

Is it bad?’ he ventured, eager to hear her interpretation. The lady reached across the table, urgently

clasping Raymond’s forearm.

‘The time is now, and the message is urgent’, she gasped as

her fingernails dug into his skin, ‘You must act now – the eye will not remain

open forever!’.

Shaking free of her grip, Raymond stumbled backwards,

knocking over his chair. Her words had

shaken him, frightened him, wound themselves around a hidden part of his subconscious

that only he could see, and he was petrified - so much so that he ran all the

way back to the house and sealed himself in his bedroom.

DAY 10

Early the next day, Percival, somewhat concerned having not

seen his housemate in some time gently wrapped upon his bedroom door.

‘Raymond? Are you

okay in there?’, he asked gently.

He was accustomed to his new friend behaving skittishly, but

this was something new. Raymond had led

such a sheltered life after all, and Percival was worried that his visit to the

Lady in Waiting had gone poorly. He lingered

a few moments, but there was no response.

‘Okay then. I just

wanted to let you know that I’m going fishing.

I’ll return when the sun goes to sleep’.

Inside his bedroom, Raymond could hear the sound of Percival

leaving the house. He’d had a sleepless

night, and he didn’t wish to burden Percival with his problems. But the Lady in Waiting’s prophecy had disturbed

him, in a manner more deeply than he’d ever known. He was still only new to his freedom, and yet

so much was being asked of him already.

So many decisions to make. Around

noon, after a few hours brooding alone, he exited and proceeded to the kitchen

where the scroll, with its single eye, was still sat upon the table. Locating a pen – an ornate one that once

belonged to Kevin - he stood before the waiting document, his arm outstretched,

determined to finally sign it.

As he forced his hand closer to the paper, his mind was aflame

with the pain of his own crippling indecision – a mental tug of war fought only

with himself. All of the questions of

the last ten days flashed into existence once more as the moment of ultimate

choice stood before him. Would signing

be the right thing to do? Did he even want to be a home owner? What if the decision he made today had

terrible ramifications later on? Could he forgive himself for making such a

grievous mistake?

As the overwhelming anxiety of the moment overcame him,

Raymond’s arms began to tremble. He sat

down on the floor, bracing his back against the wall, but soon realised that

not he – but the house – was shaking. He

cast an incidental glance over at the scroll on the table just in time to

witness the single eye at the centre of the page close, slowly and with

alarming finality. In that moment he recalled

the words of the esteemed Julius Wallwork, Esquire:

‘…Custody of the house

reverts back unto itself, and your rights as a tenant within it will be

rescinded’.

A low rumble became thunderous as plates and cups and other

sundry items flew from their perches, smashing into a million pieces as the

doors and walls of the house convulsed.

Leaping to his feet, Raymond ran from room to room, struggling to

understand the precise nature of what was happening.

Outside, the house shook itself free from its foundations

and sprouted two enormous three toed feet.

Sheathed in reptilian scales and strong enough to support the house’s

considerable bulk, the feet began walking, taking the house along with it.

Sat on her front

porch, Mrs Gale witnessed the entire occurrence unfold. She marvelled as the house next door simply

walked away on giant feet, leaving a trail of flotsam and jetsam in its

wake. As it moved, each step it took

produced a mighty thud that reverberated through the earth.

Inside the moving house, Raymond struggled to stay on his

feet, buffeted about by the turbulent journey.

He looked out a window to see a strange moving vista as the house walked

itself deeper into the woods, deftly avoiding collision with trees and bushes

as it made its way down a steep decline.

Gathering momentum, the house accelerated, moving past the hollow tree

where Raymond had been just the previous day.

Past the place where these very events had been foretold.

The journey had thus far lasted minutes, but to Raymond it seemed

like hours as the contents of the house showered down upon him as he

surrendered to unyielding terror, screaming until his voice was hoarse. Moving down into a sandy gully, the house

finally came to a complete stop, at which time Raymond, still cowering, managed

to drag himself to a nearby window in order to survey his location.

The house had taken him to a part of the woods he’d never

seen before. Mostly devoid of

vegetation, the ground appeared dry and cracked, and the landscape barren and

dotted with jagged rocks. From the vague

descriptions he had heard over the years, it could only be one place – Simian

Sands. It was indeed, a place no

sensible person would hope to find himself.

Within seconds, Raymond’s worst fears were confirmed as he heard an

awful screeching coming from outside the house, followed shortly after by a

pounding on the walls. It was the

simians, and from the sounds they produced, it sounded as though they were

numerous.

Finding his last shred of courage, Raymond sprang to his

feet and made for the kitchen, intending to find a weapon with which to defend

himself. A knife, or any other kitchen

utensil would do in a pinch. As he

entered the room, he heard the sound of shattering glass behind him as a balled-up

simian smashed his way through one of the windows. Hunched over and tightly muscled, the simian’s

teeth appeared razor sharp and his eyes were filled with blood lust. Grabbing one of the chairs from the kitchen

table, Raymond swung the piece of furniture at the horrible creature, striking

it clean across its face. No result –

the chair merely smashed into smithereens and the hideous ape only roared in

anger. It leapt forward, in one sudden

motion, its powerful hands clawing at Raymond’s face.

Soon, another simian had broken into the house, then another

and then another. All of them dove for

Raymond, who was now pinned to the floor, desperately fighting for his

life. One of the beasts latched onto his

left leg and tore it clean off, while the others used their hands to rip into

his midsection like a knife through hot butter.

In the midst of his death throes, Raymond howled out in agony, as the

simians tore him apart, limb from limb.

And that was how poor Raymond met his final end. The entire, unpleasant affair could have been

easily avoided had he simply made a decision.

He spurned the gift that had been lovingly bestowed upon him by the

universe – that of free will and choice – and lost his life as a result. For if we do not make our choices ourselves,

others will surely make them for us.